By Izzy Epstein

Eight months into the Israel-Hamas War, domestic and international political pressure is mounting for United States President Joe Biden and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to put an end to a costly war. American and Israeli leaders have a stake in planning out a future for Gaza, but for many thinking a step ahead, an overarching question remains – “Who represents the Palestinian people?” Salam Fayyad posits this question to New York Times journalist Ezra Klein, claiming that acknowledging the many answers to this predicament is the key to understanding Palestinians’ historical “struggle for freedom, for nationhood, and for self-determination.” Salam Fayyad is notable among politicians and Middle East scholars for his service as the Prime Minister of the Palestinian Authority (PA), where he instituted a nuanced approach to achieving Palestinian statehood, coined by western scholars as “Fayyadism.” His strategy has been described as “a fundamental attitudinal shift,” transitioning the Palestinian national rhetoric away from armed struggle and paralyzed negotiation processes, towards a strategy that translated into tangible improvements for the people on the ground (Danin 2011). Though his statebuilding effort was still deeply flawed and at times idealistic, his rhetoric of non-violence, pluralism, independence, and optimism still rings true today.

Who is Salam Fayyad?

West Bank-born and U.S.-educated, Fayyad has a background working for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Arab Bank before his direct involvement in Palestinian politics. In the early 2000s, he served as Finance Minister in multiple non-consecutive terms, briefly leaving the government to run for office in the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections as founder of the new ‘Third Way’ party. Fayyad was appointed as PM in the wake of the 2007 split of the Hamas-Fatah unity government, resulting in Hamas’ takeover of the Gaza Strip. President Mahmoud Abbas formed a technocratic emergency government, appointing Fayyad as the interim PM. The crisis cabinet was heavily contested to be illegal as its creation was not approved by the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), nor voted on by Palestinians themselves.

What is Fayyadism?

“A Palestinian state will never be created by terror. It will be built through reform. True reform will require entirely new political and economic institutions, based on democracy, market economics, and action against terrorism. This moment is both an opportunity and a test for all parties in the Middle East, an opportunity to lay the foundations for future peace, a test to show who is serious about peace and who is not.” George W. Bush, 2002

In its most simplified form, Fayyadism represents a response to such a Western ‘test,’ a response that differed from many of his colleagues. Though he acknowledges the inherent injustice of posing the pursuit of self-determination as something to be earned by appealing to Western standards, Fayyad believed, “fair or unfair, let’s take that test and pass it” (Fayyad 2024).

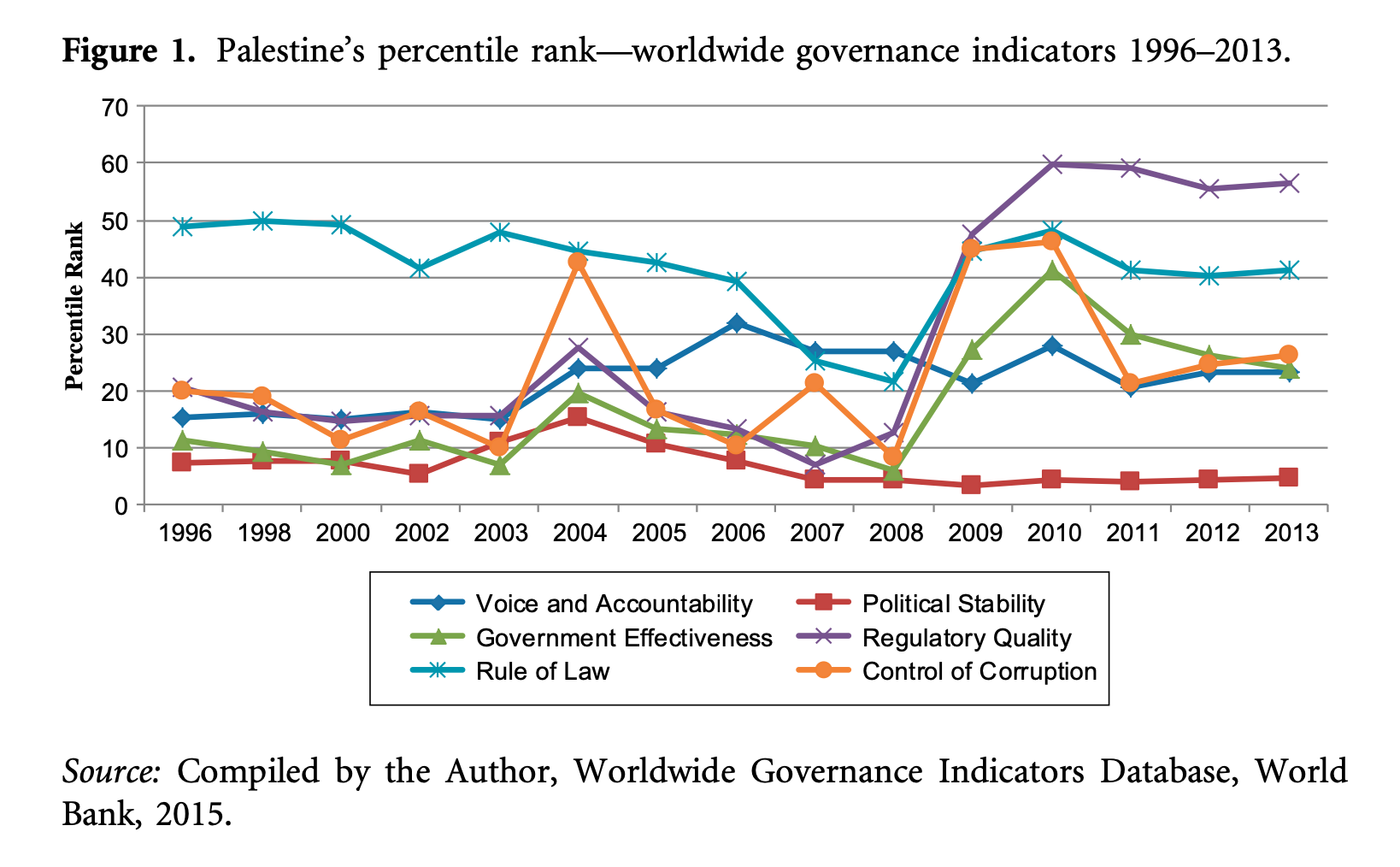

Fayyad believed he could achieve Palestinian statehood by developing and strengthening state institutions in coordination with standards set by the international community. He focused on largely four dimensions of reform, outlined in his 2008 “Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (PRDP),” and advanced in his 2009 plan, “Palestine: Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State:”

- the reform of the security sector and the enforcement of the rule of law

- the building of accountable PA institutions

- the provision of effective public service delivery

- economic growth led by the private sector in an open and free market economy

The PRDP openly acknowledges that the PA cannot make these reforms alone: “If the [Israeli] occupation regime remains unchanged, the economic outlook is extremely poor… Any reluctance or inability on the donor side to predictably finance the budget deficit over the medium term will lead to a deepening fiscal crisis that would return the PNA to the point of financial and institutional collapse”(PA 2007).

What were the results?

Fayyad’s early efforts produced measurable results on the ground.

- Economic Growth: The economy experienced a growth rate of 8.5%, growing to 9% by 2010 and 2011 (IMF 2011).

- Budget progress: In 2008, the PA narrowed the budget deficit from 29% of GDP in 2008 to 8% of GDP in 2017 (UNCTAD 2017).

- Decreased unemployment: Rates declined from roughly 20% in 2008 to 15% by 2011 (IMF 2011).

- Infrastructure development: Between 2008 and 2010, more than 120 schools were built, 1,100 miles of road laid, and 900 miles of new water networks were established. In 2009 and 2010, 11 new health clinics were establishedand 30 more were expanded (Danin 2011).

- Improved investment climate: Foreign investment in the Palestinian territories had reached USD 2.297 billion by the end of 2010, a 45 percent increase over 2009 figures (PA 2011).

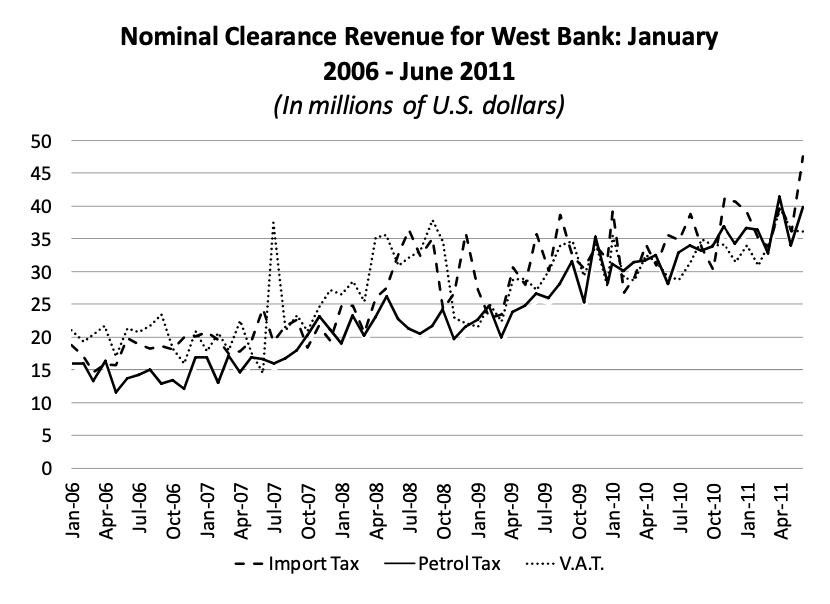

- Increased clearance revenues: The PA’s budget disproportionately relies on clearance revenues — import taxes collected by Israel on its behalf. Clearance revenues increased notably under Fayyad’s reign.

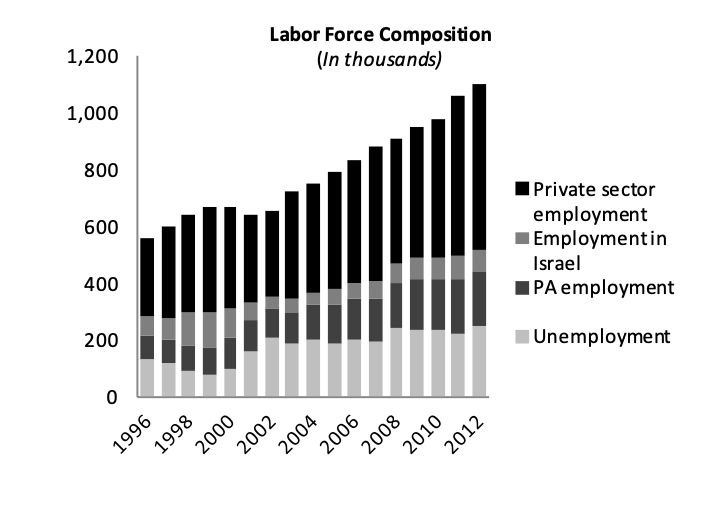

Labor Force Competition

But it also faced a number of detrimental challenges:

- Israeli restrictions: Israel exercises control over all trade into the West Bank passing through its seaports, airport, and over the Allenby-King Hussein bridge connecting the West Bank to Jordan.

- Shortfalls in aid: In 2011, the budget was based on international donor pledges of $483 million, but only about $300 million was disbursed (IMF 2011).

- Withholdment of clearance revenues: As established by the 1994 Protocol on Economic Relations, Israel can legally withhold clearance revenues from the PA, which are usually provided on a monthly basis. Israel withheld significant portions of the collected revenues as a result of attempts at internal reconciliation between Hamas and Fatah, as well as Fayyad’s pursuit for UN recognition of a Palestinian state (IMF 2011).

By 2011, Fayyad himself claimed, “The West Bank is already a state in all but name” (Fayyad, 2011). By April 2011, the World Bank had “certified” the PA as being “well positioned to establish a state at any time in the near future” (World Bank, 2011). By 2012, the United Nations offered Palestine the status of a non-member observer state in the UN General Assembly. In 2013, Fayyad resigned from his position as PM, claiming his work was done and his goals were completed.

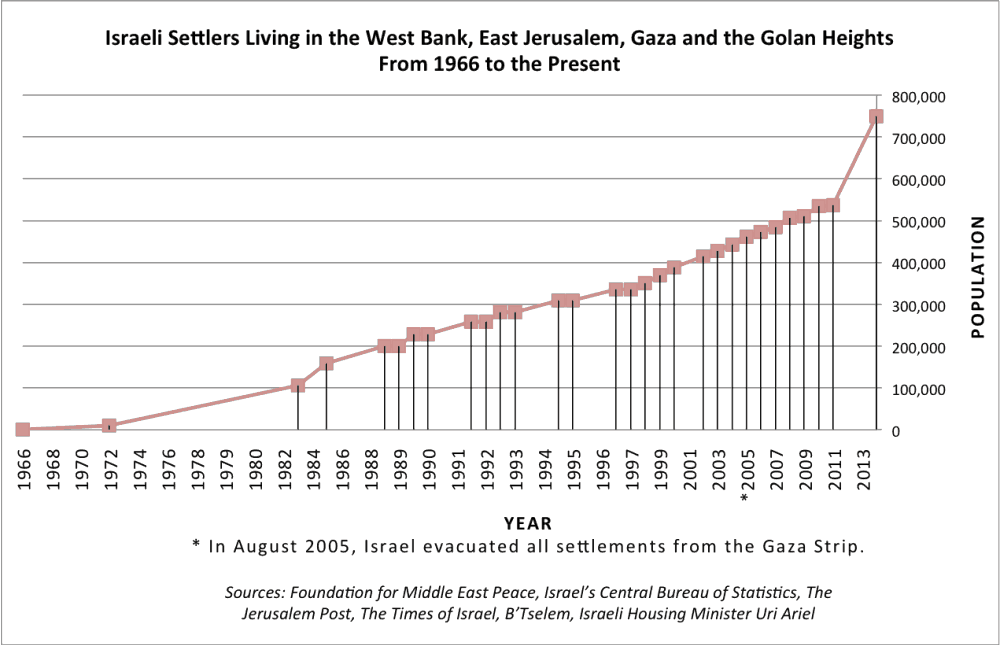

However, in the eyes of many Palestinians, Fayyad had come up remarkably short. Though Palestine experienced an elevated position in the international arena, Fayyadism underperformed in the areas that mattered most to Palestinians; similar to the Oslo process, key issues of border determination, the fate of Jerusalem, and the right to return, were once again sidelined, and to be decided by final status negotiations, which had been stagnant for six years. The institutional reforms seemingly ignored the structural realities of Israeli occupation and proved ineffective at preventing continuous military incursions by the Israel Defense Force (IDF) or sustained expansion of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories. Even if their day-to-day lives were easier, Palestinians of the West Bank continued to live under Israeli settler-colonial rule and military occupation.

While Fayyadism garnered support from the international community, Fayyad failed to translate that support into any meaningful political progress. By the end of his term, the PLC continued to be suspended indefinitely, Abbas was approaching a decade as President, there were no signs of elections for the foreseeable future, and the law of the land was still dependent on the decades-old Oslo Accords. Similarly, Fayyad struggled to garner any identifiable base of domestic support; he was relatively unknown by regular citizens of the West Bank and was not democratically elected, making the implementation of his reforms “undeniably authoritarian”(Brown 2010). Many people on the ground saw Fayyadism as a means of functionalizing and streamlining the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. As some cynical Palestinians joke, “The PA is covering the road to self-determination in asphalt.” “We have the sewers; all that’s left is the sovereignty.” “The streets of Ramallah are paved with white stones — who needs Jerusalem?” (Kanafani 2011).

While the institutional and economic progress facilitated by Fayyadism was admirable, it did not “even pretend to offer a solution for the deeper problems afflicting Palestinian politics—division, repression, occupation, alienation, and wide-reaching institutional decay” (Brown 2010). Fayyadism attracted interest from international actors but did so without the consent or consideration of the Palestinian people. The implementation of Fayyad’s reforms indeed failed to have a lasting impact on the West Bank and largely fell apart after he left office, as he had few allies in the government or on the ground.

What can we learn from it?

In the midst of the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, Fayyadism should emphasize to us that governance that excludes Palestinian voices and prolongs political progress is unlikely to be successful or sustainable. It shows us the stabilizing power of strong institutions, but reminds us that “for those institutions to function properly, they must have domestic political support and legitimacy…they must be seen as working for and not against Palestinian basic aspirations”(Elgindy 2013).

While Fayyadism failed in many ways, Fayyad represents a rare manifestation of Palestinian leadership, one that is unequivocally committed to non-violence, pragmatism, and Palestinian self-reliance. Unlike many scholars, Fayyad has a tangible idea of what governance of Gaza will look like after the war, one that seems to acknowledge and address his shortcomings as PM. As the PA is widely considered a corrupt failure, and Hamas is seen as fundamentally violent, Fayyad insists on a radical reconstruction of Palestinian leadership. He suggests that “the first step must be the immediate and unconditional expansion of the PLO to include all major factions and political forces, including Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad”(Fayyad 2023). Fayyad believes that this process would have to begin with a formal recognition by Israel of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination of a sovereign state based on the pre-1967 armistice line. With a government appointed by the PLO, the PA would then be given full jurisdiction of Palestinian affairs in Gaza and the West Bank through a multiyear transitional period set on a definitive timeline, which includes a date for national elections.During this time, Israel and the PA would be united in “an ironclad mutual commitment to nonviolence” that would continue until a final settlement is reached (Fayyad 2023). Learning from his mistakes, Fayyad does not have any plans of doing this alone, claiming that no ‘day after’ governance of Gaza will be possible with significant help from the international community and the legitimacy provided by the approval of other Arab States.

Given that a permanent ceasefire and a joint commitment to non-violence is a precondition to Fayyad’s ‘day after’ plan, a lot needs to happen before any such developments come to fruition. Regardless, Fayyad emphasizes that such commitments to non-violence are not hopeless. “[Violence] was part of the P.L.O.‘s identity up until they signed that piece of paper in 1993…You can’t label a faction as forever being one thing or the other. And history is replete with examples like this” (Fayyad 2024). Despite Fayyad’s pragmatic optimism, he doesn’t believe that peace in and of itself will solve all of the problems brought to light by this war: “After all, when peace is made, it’s not exactly made between good neighbors and happy neighbors…The deep scars of this war are going to last forever and ever”(Fayyad 2024). Though the means by which this war will end are not to be decided by outsiders like Fayyad, he knows that continued violence will not leave either side victorious. He claims, “Hamas has an ideology, it’s a political movement — and the only way you can compete with an idea is with a better idea.” Unlike many others, Fayyad offers such an idea, and as hopeless as matters may look, it is in Israel’s best interest to accept Fayyad, or a leader like him, to be the partner for a lasting peace.

Sources

Brown, N. J. (2010a, September 17). Fayyad Is Not the Problem, but Fayyadism Is Not the Solution to Palestine’s Political Crisis. Carnegieendowment.org. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2010/09/fayyad-is-not-the-problem-but-fayyadism-is-not-the-solution-to-palestines-political-crisis?lang=en

Brown, N. J. (2010b). The Hamas-Fatah Conflict: Shallow but Wide. The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, 34(2), 35–49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45289503

BUREAU OF ECONOMIC AND BUSINESS AFFAIRS. (2012, June). 2012 Investment Climate Statement – West Bank and Gaza. U.S. Department of State. https://2009-2017.state.gov/e/eb/rls/othr/ics/2012/191264.htm

Bush, G. W. (2002, September 17). The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Archives.gov; The White House. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/nsc/nssall.html

Danin, R. M. (2011). A Third Way to Palestine: Fayyadism and Its Discontents. Foreign Affairs, 90(1), 94–109. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800384?searchText=&searchUri=&ab_segments=&searchKey=&refreqid=fastly-default%3A520aab6c7818b6b0418a8bf5033289a2&seq=1

Elgindy, K. (2013, April 22). The End Of “Fayyadism” In Palestine. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-end-of-fayyadism-in-palestine/

Fayyad, S. (2023, October 27). A Plan for Peace in Gaza. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/israel/plan-for-peace-gaza-fayyad?check_logged_in=1&utm_medium=promo_email&utm_source=lo_flows&utm_campaign=article_link&utm_term=article_email&utm_content=20240630

International Monetary Fund. (2011a). Recent Experience and Prospects of the Economy of the West Bank and Gaza Staff Report Prepared for the Meeting of the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee. https://www.imf.org/-/media/external/country/WBG/RR/2011/091411.ashx

International Monetary Fund. (2011b). West Bank and Gaza: Recent Developments in Clearance Revenues. https://www.imf.org/-/media/external/country/WBG/RR/2011/102711.ashx

International Monetary Fund. (2012). West Bank and Gaza: Labor Market Trends, Growth and Unemployment A. Labor Market Trends since Oslo 2. https://www.imf.org/-/media/external/country/WBG/RR/2012/121312.ashx

Klein, E. (2024, February 9). Opinion | Building the Palestinian State With Salam Fayyad. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/09/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-salam-fayyad.html?showTranscript=1

Palestinian National Authority. (2008, January 1). Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (PRDP) (2008-2010) – Palestinian Authority – Non-UN document. Question of Palestine. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-208834/

Tartir, A. (2015). Securitised Development and Palestinian Authoritarianism Under Fayyadism. Conflict, Security & Development, 15(5), 479–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2015.1100016

Ufheil-Somers, A. (2011, September 22). As If There Is No Occupation. Middle East Research and Information Project: Critical Coverage of the Middle East since 1971. https://merip.org/2011/09/as-if-there-is-no-occupation/

UNCTAD. (2019). The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: Cumulative Fiscal Costs. United Nations. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsapp2019d2_en.pdf

Wase, A. (2024, May 1). Former Palestinian prime minister Salam Fayyad commends campus activism. The Stanford Daily; Stanford University. https://stanforddaily.com/2024/05/01/former-palestinian-prime-minister-salam-fayyad-commends-campus-activism/

World Bank. (2011). Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process Palestinian State-building: a Decisive Period. http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/world/UN-Report-Palestinian-Building-April2011.pdf