Founded in 1872, Rex still parades as one of the lasting old-line krewes. Its original parading colors: purple, green, and gold, were adopted by the entire carnival and are still the standard today. Rex’s title as ‘King of Carnival’ began at its first parade and still continues. The krewe originated as an all-white male krewe, with women only performing traditional female roles behind the scenes. Despite its influence, Rex has a complicated relationship with New Orleanians and other krewes because of its values that encourage exclusivity. Unlike many Mardi Grad krewes, Rex does not seek members or encourage external participation, but its members are those who have generational connections or have accumulated wealth and influence within the New Orleans community. Not only are connections necessary to be a part of Rex, but one must be able to financially support the significant cost of being part of the krewe and the even larger cost of being Rex himself. The major requirements, mostly achieved by birthright, to be part of the krewe make it inaccessible to the majority of Mardi Gras participants. Rex’s values are reflected in its outward presentations through floats and throws with classical themes and elaborate invitations to accompany grand balls.

In the next chapter of its existence, the krewe is focused on making a positive impact in the New Orleans community. Although Rex has an elite reputation, its traditions helped shape the celebration of Mardi Gras into what it is today, making the krewe one of the most significant and influential participants in Mardi Gras history.

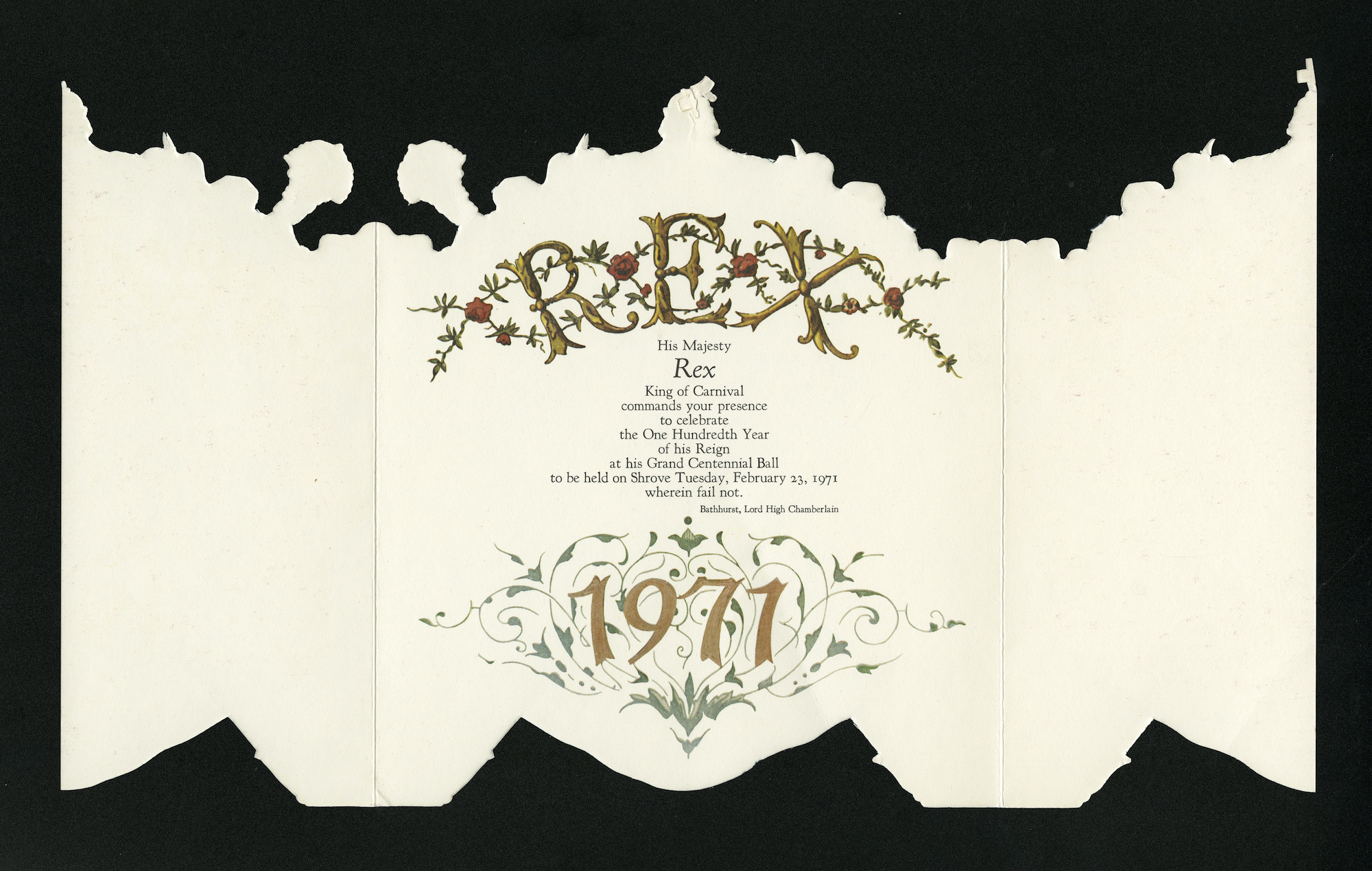

1971 Ball Invitation

By Emma Rode

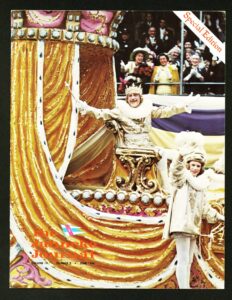

Cover, Rex 1971 invitation pamphlet, Carnival collection, LaRC-900, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Interior, Rex 1971 invitation pamphlet, Carnival collection, LaRC-900, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

One aspect of Rex that has become a significant tradition for many krewes are Mardi Gras Balls. The Rex ball invitations are elegantly crafted and a rare find as you must be invited to the ball by a Rex member. A description from the krewe itself states, “the Rex Ball brings Mardi Gras to a glittering conclusion, combining music, traditional pageantry, processions, marches, and dancing”. Rex, King of Carnival, invites his subjects to the theatrical celebration that is Carnival. During the ball, his majesty Rex, along with his Queen, is presented to the guests. The Rex Court includes Rex, his Queen, eight maids, and eight dukes.

Over the years, the Rex Ball has developed elegant traditions and a formal protocol. Attendance is of course invitation only. Each year, the design of the invitation changes, always incorporating the parade’s theme. The invitations are given to Rex members for the guests of their choice. Members and guests in attendance must wear formal attire: floor-length gowns for ladies and white tie and black tails for men. An article written about the Krewe of Rex explains, “The Rex Ball, in keeping with the organization’s more public role, was not a masked ball, but rather a formal presentation of Carnival Royalty, followed by grand marches and general dancing. Elaborate ball invitations were created each year, and have become sought-after and valuable remembrances, another tradition that continues today” (Rex Parade New Orleans)>.

When observing the artifact, one cannot help but notice its lavish decoration and imperial shape. It opens up exposing three panels. The word “Rex” and the year “1971” catch the viewer’s attention first, highlighting the importance of the krewe and year of celebration. The invitation reads, “His Majesty Rex King of Carnival commands your presence to celebrate the One-Hundredth Year of his Reign at his Grand Centennial Ball to be held on Shrove Tuesday, February 23, 1971, wherein fail not”. The invitation then reveals the current king of Rex, Bathhurst Lord High Chamberlain.

In an article written about the Krewe of Rex, Frank DeCaro comments, “…the organization established purple, green, and gold as the colors of Carnival…The organization also created the fiction that its monarch, Rex, chosen annually from among members, was the ruler of the festivities and of the city for a day…”. These colors described in the quotation are all present on the invitation at hand. From the invitation, we can tell that the senders of the invitation are proud of what they are promoting. It feels as if the handler of the invitation should be gracious to be viewing it.

Describing the impact of the Krewe of Rex on Carnival, DeCaro also notes, “The Rex parade, first staged in 1872, eventually became the centerpiece of Mardi Gras festivities, its monarch dubbed “King of Carnival.” This information is evident from the invitation artifact. The Krewe of Rex is the centerpiece of Mardi Gras. This krewe has served as the icon for Carnival productions and led as an example for other krewes. The self-declared notion of Rex as the ‘King of Carnival’ has been widely accepted and respected. The invitation is extravagant and quite impressive. This artifact is able to tell us so much about the Krewe of Rex and the impact they have on the celebration of Mardi Gras.

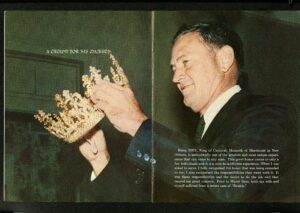

1966 Journal

By Abigail Coleman

Rex 1966 Pamphlet “The Jahncke Journal,” Carnival Collection, LaRC-900, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

Interior, Rex 1966 Pamphlet “The Jahncke Journal,” Carnival Collection, LaRC-900, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

Another artifact that sheds light on Rex is a 1966 journal recounting the duties and preparations necessary to take on the title of Rex himself, allowing a more detailed inspection of the inner workings of being ‘Rex’ and all of the preparation that it entails. Known by many as elegant, elite, and spectacular, a closer look will reveal the deeper rooted sexism, racism, and classism on which the krewe founded itself.

The artifact gives much insight into krewe’s priorities. It is no surprise the honor being selected as Rex endows. Herbert Jahncke, 1966 Rex says, “Being REX, King of Carnival, Monarch of Merriment in New Orleans, is undoubtedly one of the most unique experiences that can come to any man.” Jahncke came from a long line of rex ancestors, each having their own place in the krewe’s royalty. Familial connections play a keen role in the hierarchy of both krewe participation and even selection to join the krewe, something the old-line krewes have in common. While Rex’s response to a 1992 anti-segregation city ordinance directed at Mardi Gras krewes was to integrate nominally, it remains an all-male organization, with women’s roles subordinate to the men’s active participation (Wade 27). Robin Roberts analyzes the female relationship to the Krewe of Rex saying, “Rex is an all-male krewe, the Queen is literally an adjunct rather than a member of the krewe” (Roberts 314). This notion is very clearly demonstrated in the artifact as it notes the queen’s role in the parade being one of backstage preparations. The queen is less of a royal figure and more of a statue to stand beside the king, who’s only true significance is her connection to the king.

As James Gill explains, “To reign over the Rex parade, as king of all carnival” is “the highest honor of Mardi Gras” (7). Gill notes that there is no greater title, but with great power comes great responsibility. Though praised on Mardi Gras day, much preparation goes into the day running smoothly. According to 1966 King, preparations began several months before the carnival season even began. Janacke notes that a twelve-page manual must be carefully read and followed. The Krewe of Rex prides itself in every meticulous detail, something which arguably keeps its place on top.

One can tell from both the artifact and substantiate sources the unspoken requirement for wealth. Though never explicitly stated, many know truly how costly being king is. Many accept this willingly because of the social stature of the title. Since you must be wealthy to be a member of Rex, “the krewe reminds New Orleanians of its everyday power structure and the dominance of elite white men” (Wade 27). From the inside, however, the krewe prides itself on its motto, “pro bono publica,” for the public good. Whether the krewe abides by its motto depends on who you ask. Rex does in fact make substantial charitable donations to local causes and especially to education. Some argue that this is merely to keep up appearances, and the real motive remains difficult to discern.

The artifact sheds light on the Krewe’s own oblivion, or lack of desire for change, to the obvious disparities in their krewe. It is difficult to tell which is worse. From the obvious sexism in only allowing women subordinate positions to the classism demonstrated in the lofty fees and fiscal requirements to generate throws, it is obvious Rex has an ideal targeted member.

1897 Ball Invitation

By Matt McDonald

Rex 1897 invitation pamphlet, Carnival Collection, LaRC-900, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

While Rex helped develop the controversial traditions of modern Mardi Gras, the Mardi Gras celebration has existed long before the founding of New Orleans and has roots that can be traced back to the Romans and the Greeks. Not only are there traditions that have lasted over two thousand years, but many artifacts and pieces from Mardi Gras–specifically from the Krewe Rex–allude to these ancient times.

The most notable shared similarity between Mardi Gras and the Romans is the festivals themselves. The Roman festival of Saturnalia, honoring Saturn, celebrated the death and rebirth of nature. Although this festival was held in December, it incorporated a mock king that presided over the festival. According to Britannica, “All work and business were suspended. Slaves were given temporary freedom to say and do what they liked, and certain moral restrictions were eased. The streets were infected with a Mardi Gras madness; a mock king was chosen; the seasonal greeting of Saturnalia was heard everywhere.” This festival can see many comparisons with modern-day Mardi Gras, and even more so, draws clear comparisons to the Krewe of Rex, where they similarly name a “king” for the year’s carnival. Another noteworthy ancient festival was the Athenian celebration of Dionysus, also known as “Greater Dionysia,” which was to honor the Greek god of wine. Taking place in the Spring, this festival would include all Athenian citizens–although it’s debated whether women were allowed. According to Brown University, “Although the plays changed, this festival of renewal would remain the same…Dithyrambs would be sung by choruses…This would all be accompanied by generous amounts of wine and overall lechery.” This celebration would continue for days, and as noted above, drinking wine was an essential part of the festival. Dionysus is still a rather important idea in Mardi Gras, as in 2015, the Krewe of Endymion had a “Journey of Dionysus” as one of their floats–honoring the ancient god.

Looking more specifically to this Rex Artifact, there are many allusions to classic Greek Gods and mythology. Made in 1897 for the March 2nd ball, this invite gives insight into the theme of that year and what mythology represents to the Krewe of Rex. On the Water–Real and Fanciful–was the theme chosen for that year. In the first picture, located on the right, is a depiction of Cerberus. Referred to as the hound of Hades, Cerberus is the watchdog of the underworld and allows people to enter but never to leave. This reflects Rex’s theme for the year, as right next to Cerberus is a king, something that is real, while Cerberus is perceived as something fanciful. The artifact depicts what is believed to be Dionysus as he appears to be holding a cornucopia of grapes. Dionysus’s winemaking and wine of fertility, insanity, ritual madness, festivity, and theatre combine to make him a god that is worshipped, and many of these qualities can still be found at Mardi Gras. The excitement and satirical plays combined with the heavy drinking of wine and the days of celebrations draw many similarities. Once again Rex is playing into their theme, as one slide is fanciful (Dionysus) and the other two are real (the kings on thrones). The allusions to classical Greek mythology show that Rex cares about tradition, and they are trying to incorporate these pagan rituals into the Mardi Gras tradition. Mardi Gras is one of the few festivals left where tradition is paramount, as the Krewes often and still use many of these Greek and Roman influences. As the pagan religion of the Greeks and the Romans slowly phased out over centuries, many remnants of this ancient time can still be found in the modern world. Festivals like Saturnalia and Dionysus inspired many traditions that Mardi Gras tries to hold onto, and without it, they may forever be lost. Krewes like Rex and Endymion play an important role in keeping this tradition, as it’s up to them to remember the ancient roots that led to the Mardi Gras creation.

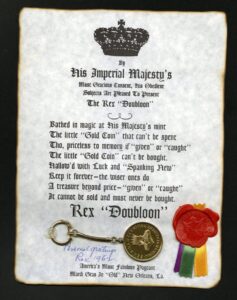

1962 Gold Doubloon

By Kyra Hudson

Rex 1962 keepsake doubloon, Carnival Collection, LaRC-900, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

Rex’s lasting impact is seen through its effect on Mardi Gras as well as the objects the krewe has left behind over the years. Its gold doubloons have gained prestige over the years for their uniqueness and status symbol. To illustrate, Rex’s 1962 gold doubloon and personal greeting that accompanies it shines a light onto the krewe. The doubloon is presented on a paper meant to look worn with the edges intentionally burnt. The personal greeting is written in a highly embellished script and a printed crown. The message is stamped with the official seal of Rex and ribbons in the krewe’s signature colors. The greeting reads, “Bathed in magic at his Majesty’s mint/ The little ‘Gold Coin’ that can’t be spent/ Tho, priceless to memory if ‘given’ or ‘caught’/ The little ‘Gold Coin’ that can’t be bought/ Hallow’d with Luck and ‘Spanking New’/ Keep it forever – the wiser ones do/ A treasure beyond price – ‘given’ or ‘caught’/ It cannot be sold and must never be bought” (Personal Greeting 1962).

As seen through the message that they sent out to those they deemed fit to possess their doubloon, the krewe thinks very highly of themselves and their king. The capitalization of majesty shows how the krewe believes Rex to be the superior and true king of Mardi Gras. Additionally, this message highlights their value of status and their desire to keep the members of the krewe highly connected and elite members of New Orleans society. Rex wants his doubloon to stay in the hands of those who received it and does not want others to be able to gain access to it. While this may seem like a playful jest to stress the remarkability of the doubloons, its exclusive undertones are true to the values of the krewe. Members of Rex are typically only able to enter because of family connections and family wealth. Rex is both highly exclusive and incredibly costly. It costs thousands of dollars to be a member of Rex, to be on the court, and even more to be Rex (Roberts 317). People who are involved in the krewe have to have such an elite and privileged status that it is almost impossible for outsiders to maintain the requirements of the krewe even if they were allowed to enter. The 1962 doubloon and personal greeting not only show the exclusivity of Rex but the gaudiness and excessiveness of the krewe. The formal language, alterations to the paper, and overall details were most likely an attempt to make the greeting seem old and important as if a true king sent it. This once again stresses the idea that members of the krewe do not see Rex as a figurehead of a celebration, but as the true king of Mardi Gras (Rex Organization). Their belief that Rex is a king is a direct cause for much of their gaudiness. Its power lies in its status as an old-line krewe, but also its gaudy persona of Rex and extreme displays of wealth in attempts to create envy among other Mardi Gras participants (Atkins 5).

Sources

“Atkins, Jennifer. “‘Using the Bow and the Smile’: Old-Line Krewe Court Femininity in New Orleans Mardi Gras Balls, 1870-1920.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 54, no. 1, 2013, pp. 5–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24396434. Accessed 7 Oct. 2020.

De Caro, Frank. “Mardi Gras in New Orleans.” 64 Parishes, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 25 Sept. 2020, 64parishes.org/entry/mardi-gras-in-new-orleans.

Gill, James. Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans. University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

“Great Dionysia.” Great Dionysia, Brown University, Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology, www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/13things/7411.html.

Kolb, Carolyn. New Orleans Memories: One Writer’s City. University Press of Mississippi, 2013. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tvn7z.

“Mardi Gras History.” Mardi Gras New Orleans, www.mardigrasneworleans.com/history/.

“Mardi Gras History and Traditions.” Mardi Gras Traditions,

mardigrastraditions.com/mardi_gras_history/.

“Rex Parade New Orleans.” Parade New Orleans, www.neworleans.com/event/rex/3389/.

Roberts, Robin. “New Orleans Mardi Gras and Gender in Three Krewes: Rex, the Truck Parades, and Muses.” Western Folklore, vol. 65, no. 3, 2006, pp. 303–328. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/25474792. Accessed 22 Oct. 2020.

“Saturnalia.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.,

www.britannica.com/topic/Saturnalia-Roman-festival.

Spitzer, Nick. “Mardi Gras Celebrations.” The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 14: Folklife, edited by GLENN HINSON and William Ferris, by Charles Reagan Wilson, University of North Carolina Press, 2009, pp. 152–157. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807898550_hinson.33. Accessed 8 Oct. 2020.

Tallant, Robert. Mardi Gras. Doubleday, 1948.

Wade, Leslie A., et al. Downtown Mardi Gras: New Carnival Practices in Post-Katrina New Orleans. University Press of Mississippi, 2019.