Established in the early twentieth century as a social club and form of insurance for the African American community, Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club was inspired by a musical comedy “In Zululand,” more specifically one of the skits “There Never Was and Never Will Be a King Like Me.” In these times, by dressing in blackface, Zulu was able to reclaim the practice of using blackface, which old-line krewes had traditionally practiced, portraying caricaturized images of the African American community.

1941 Pamphlet

By Drew Kauffman

1941 Pamphlet, Ephemera Collection, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

The 1941 Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure club pamphlet from the Tulane University Mardi Gras Archives show us the history of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club in addition to some of the controversial traditions tied to the krewe. In this pamphlet, we see names and pictures of the 1941 members of Zulu as well as past Zulu kings and queens, a brief history of Zululand, a history of Mardi Gras, and information about the 1941 Zulu parade.

A main part of the pamphlet describes Zulu’s history as well as its ties to Mardi Gras. In the section describing the krewe of Zulu’s connections to the Southeastern African tribe of Zulu, the two groups are compared, describing the entrance of the Zulu King to Zululand for each group where the New Orleans Zulu resulted in far more celebrations. This section makes comparisons and also notes differences between the two groups in order to set a hierarchy. For example, Kevin McQueeney points out that the Zulu krewe uses the face of the Zulu tribe, who were portrayed to be savage warriors, which is shown in many of the pictures in the pamphlet. McQueeny argues that they did this to show that the members of this African American krewe aren’t the lowest on the hierarchy; it gives them some sort of superiority over the African warriors when they were being discriminated against by the white krewes.

In this pamphlet, it is necessary to point out the blackface that is depicted in many of the pictures provided. Although it is a tradition among the krewe, it still remains highly controversial to this day. However, according to Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen, the act of black face among the krewe is used as a sense of empowerment as well as satirizing the so prevalent racism seen around them. The use of exaggerating African features, as Taylor and Austen explain, is something more than just funny costumes and having fun during the parades. This minstrelsy’s purpose was “calling attention to racist stereotypes by vivifying them” (Taylor and Austen 89). Furthermore, Zulu aimed this satire specifically at “white carnival” , which was known to use blackface simply to make fun of African Americans. Blackface in Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, whether some people agree with it or not, is a part of Zulu tradition and shows us that this krewe doesn’t stand for blatant racism, as seen so often especially around the krewe’s founding and the production of this pamphlet in 1941.

Although Zulu has a satirical aspect of the krewe with blackface to poke fun at the white krewes exaggerating African features, a huge part of Zulu is the acceptance of all people, no matter the race or color. According to McQueeney, “Zulu, however, continues to employ the practice and finds many defenders in the New Orleans white and black community.” This universal support is seen in a couple of the pictures in the pamphlet as some of the people pictured are white as the krewe welcomes all races to celebrate with them. In addition to this, the pamphlet also includes a section that talks about how the 1941 parade will be the first to allow the white population as well as the general public to view the voodoo ritual. This ritual is an example of how Zulu isn’t an exclusive krewe to those of a specific race or gender. They are open for all people to celebrate and take part in while also emphasizing its roots in racial equality and justice. Even women being part of the krewe was relatively new in 1941. According to Charles Chamberlain, before 1933, Zulu was an all-male krewe. This is even more proof to show us that Zulu is a dynamic krewe and will shift its ideals throughout time with what is acceptable in society.

This pamphlet shows us that even in 1941 near its founding, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club was accepting of all people as opposed to some krewes that won’t accept women and would rather not parade than publicly say they’re against racism.

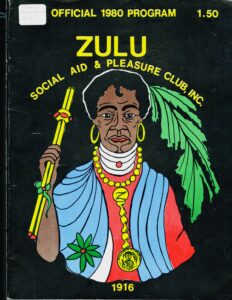

Official 1980 Program

By Hannah Levitan

Official 1980 Program, Ephemera Collection, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Despite its name, Zulu does not claim to be an African-themed parade, rather an organization that “proudly proclaims its origins in American blackface minstrelsy” (Smith 24). Evidently, segregation played crucial roles in the formation and development of Zulu. As a result of the white flight in the 1960s and 1970s, New Orleans became a predominantly African American community in the early 1980s, allowing the organization to expand its influence.

Zulu’s official 1980 program features an illustration of Zulu’s 1916 King, John White, holding a golden scepter and wearing gold jewelry, accessories that were an early spoof on the Rex krewe. Following their first march in 1909, “Zulu rode on floats in 1915, and were incorporated as an organization in 1916– they didn’t create a Carnival ball ritual until well into the twentieth century, perhaps signifying their reluctance to incorporate old-line practices into their own rituals” (Atkins 156). The program pictures White, arguably alluding to the power dynamic shift following white flight. This simple cover illustration signifies Zulu’s ability to reclaim their community’s traditions, controversial or not.

The program contains a letter from New Orleans’ first African American mayor, Ernest Morial, who was a leading civil rights advocate. Morial first took office in 1978 and, ironically, had been the NAACP leader during the 1963 boycott of Zulu. However, despite his original view of the krewe as a caricature of the African American community, “Morial needed every black vote in his contest against an experienced and well-financed white opponent. Black community arguments over what, if anything, Zulu’s parade represented were increasingly shelved in the pursuit of a united African American political front” (Smith 31). Following Morial’s success in office, he later stated in Zulu’s official 1985 program that he was a “proud and active member of the Zulu Social and Pleasure Club.” Once serving as a form of insurance for the African American community, Zulu had evolved into a means of political change.

On the next page in the program, city councilman and krewe member Roy E. Glapion responded to the question “What Does Mardi Gras Mean To You?” After Mardi Gras was cancelled in 1979, “Mardi Gras 1980 proved to be a rebirth” (Laborde 149). Glapion writes that the “beginning of [the] decade is filled with difficulties and inflationary strife.” Referring to the police strike that occurred the year prior and cancelled Mardi Gras, New Orleans had the opportunity to restructure their community.

Zulu’s official 1980 program reveals the krewe’s significant role amidst political unrest both at its birth in 1909 and “rebirth” in 1980. Filled with sentiments from previous years, Zulu’s program illustrates their humble beginnings and evolution into a major krewe. While the formation of an African American krewe did not eliminate Mardi Gras’ elitist reputation, Zulu continues to play a significant role in both the greater New Orleans and African American community.

Zulu Coconut

By Sara Hagstrom

Zulu Coconut, Carnival Collection, LaRC-9002, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Mardi Gras is celebrated by people all around the world, but the sheer extravagance of the Mardi Gras celebration in New Orleans is one that cannot be matched. While the glitz and glamour of carnival draws in tourists from all around the world, few are aware of the social culture of historic New Orleans that is at the foundation of Mardi Gras. As krewes parade down city streets in their eye-catching floats, they do so with the purpose of representing their identity. Each krewe has their own story, which they tell through their costumes, floats, and throws.

I chose to focus my research on a decorated Zulu coconut from 1979. The Zulu coconut is representative of the history behind the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, its members, and the history of racism in New Orleans.

The Zulu coconut is one way the krewe displays their theme of white stereotypes surrounding African life. The krewe of Zulu is not related to the African tribe of Zulu. The skit represented minstrel style theater where actors in the skit wore “blackface and dressed in grass skirts” to display the typical stereotypes surrounding African life (Smith). During this time, African American performers began dressing in blackface in order to obtain ownership over the typical African American characters being portrayed by whites. Similar to the way African American performers were taking back their identity in the theater, the krewe of Zulu was formed to reclaim the use of blackface in Mardi Gras, which had traditionally been used by old-line krewes and white revelers.

Every year, Zulu features the characters of “the Big Shot, the Witch Doctor, the Ambassador, the Mayor, the Provident Prince, the Governor, Mister Big Stuff, and the King’s personal guard, known as the Soulful Warriors” in their parade (Costello 32). These characters stand to parody the roles presented within white krewes while also playing into society’s stereotypical image of uncivilized African men. Members who are not assigned a specific character wear “grass skirts, wigs, and black thermal underwear and blackened their faces to lampoon whites’ conception of Zulu warriors” (Costello 32). The Zulu coconuts are just another element that plays into this portrayal and are symbolic of the power that Zulu members have reclaimed over whites’ ability to shape the identity of African Americans in society.

In addition to the displaying the krewe’s message, the coconut also alludes to African Americans’ low economic status in the early 20th century. Since glass beads were expensive, the krewe decided to throw coconuts because their jobs working at markets in the French Quarter enabled them to purchase coconuts at a low price. In fact, before Zulu threw coconuts, they used to throw walnuts because they were more affordable than coconuts (Owens). The Zulu coconut is symbolic of the economic discrimination African Americans’ have faced throughout history and the obstacles they have overcome to participate in Mardi Gras.

Every year members of Zulu hand decorate these coconuts with paint and glitter. The decorated coconuts are drained of milk and scraped of the meat to make the coconuts lighter and last longer, which is important considering they are “intrinsically the coolest throw ever” (Stroup). The Zulu coconut is one of the most highly sought after throws of Mardi Gras, which is a reminder of how Zulu has evolved from being a group of poor laborers to an influential, prominent Mardi Gras krewe.

The glittery, one of a kind, Zulu coconuts are undoubtably valuable; however, beneath the glitter and the paint, each coconut tells the story behind the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. At its core, the coconut is symbolic of history of racism towards African American’s in New Orleans and their journey to assert their status in the Mardi Gras community.

Zulu Tambourine

By Madeline Dacre

Zulu Tambourine, Carnival Collection, LaRC-9002, Tulane University Special Collections, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club is one of the most prominent krewes in Mardi Gras today. They were the first Mardi Gras parade by African-Americans, they were the first to have a signature throw (the treasured coconut), and the first krewe to feature a celebrity as their king (Hardy, 59). However, this section will be focused on a different throw: a tambourine. How is this throw just as telling of the krewe as the beloved coconut?

Inspired by a musical skit, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club was officially established in 1916. Zulu caricatured Rex; “If Rex held a scepter, Zulu held a ham bone. If Rex had the city police marching before him, Zulu had the Zulu police–wearing police uniforms until the municipal authorities objected” (Mitchell, 151).

With the history of Zulu being established, the history of the tambourine can be understood more clearly. As mentioned before, on the face of the tambourine is Zulu’s 1916 King, John White. Now, “…the Zulu Krewe’s dress accoutrements – raggedy pants, grass skirts, a king carrying a banana-stalk sceptre and wearing a lard can crown – bore no similarity to Zulu regalia, some have observed that the Krewe’s formation was in reality a biting social commentary on white domination and stereotypes of Africans and people of African descent” (Vinson, 54). While there is not a direct relationship or direct line of descent with the Zulu people of South Africa, it is obvious that the Krewe of Zulu is loosely based on their culture. City Councilman Jay Banks, who served as a one time Zulu King, has stated, “…[the costumes] pay homage to the Zulu of southern Africa…” (Krupa).With this in mind, it is clear that the tambourine is showing us the relation of how the Zulu people in South Africa inspire the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. The imagery of John White on the face of the tambourine is clear; he has a banana stalk sceptre. He has a palm leaf in his hair.

However, this tambourine can also show us the importance of music, not only in New Orleans culture, but also in Black New Orleans culture. The tambourine not only appeals to the black community, but also to other people in the parade. Everyone wants to receive a throw during a Mardi Gras parade, and the tambourine is impartial to everyone. As many of us know, music is heavily significant and prevalent in New Orleans. This artifact shows us the importance of music, not only to Zulu, but the black community they help to represent and stand for.

In conclusion, this artifact tells us many different things about the Krewe of Zulu. It tells us that Zulu will always be a king, and how they depict themselves as one; this is depicted by the banana stalk sceptre and how the king holds it on the tambourine, and how he is wearing red and gold, which are colors of royalty. The artifact also tells us how the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club was inspired by the Zulu culture of the people in South Africa. This is seen by all the imagery on the tambourine itself. The tambourine can also tell us about the importance of music and instruments to New Orleans culture, and especially to black New Orleans culture. While this tambourine may not be as coveted or beloved as the Zulu coconut, it can tell us much about the background and outlook of the social aid and pleasure club.

Works Cited

Atkins, Jennifer. New Orleans Carnival Balls: The Secret Side of Mardi Gras, 1870-1920. Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

Chamberlain, Charles. “From Tramps to Kings: Celebrating One Hundred Years of Zulu: 1909-2009.” 64 Parishes, 1 Sept. 2017, 64parishes.org/from-tramps-to-kings-celebrating-one-hundred-years-of-zulu-1909-2009.

Costello, B. J. Carnival in Louisiana: Celebrating Mardi Gras from the French Quarter to the Red River. Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

Hardy, Arthur. Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Arthur Hardy Enterprises, Inc., 2007.

Kinser, S. Carnival, American style: Mardi Gras at New Orleans and Mobile. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

“Krewe of Zulu: Mardi Gras New Orleans.” Krewe of Zulu | Mardi Gras New Orleans, 1996, www.mardigrasneworleans.com/parades/krewe-of-zulu.

Krupa, Michelle. “The black leaders of an iconic Mardi Gras parade want you to know their ‘black makeup in NOT blackface.” CNN, 5 Mar. 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/16/us/zulu-new-orleans-blackface/index.html. Accessed 7 Oct. 2020.

Laborde, Errol. Mardi Gras: Chronicles of the New Orleans Carnival. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2013.

McQueeney, Kevin. “Zulu: a transnational history of a New Orleans Mardi Gras krewe.” Safundi, vol. 19, no. 2, 2018, pp. 139-163.

Mitchell, Reid. All on a Mardi Gras Day: Episodes in the History of New Orleans Carnival. Harvard University Press, 1995, pp. 147-191.

Owens, K. Throw me somethin’ mister! The history behind New Orleans Mardi Gras. Retrieved October 08, 2020, from https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/throw-me-somethin-mister-history-behind-new-orleans-mardi-gras-throws.

Smith, Felipe. “Things You’d Imagine Tribes to Do: The Zulu Parade in New Orleans Carnival.” African Arts, vol. 46, no. 2, 2013, pp. 22-35. UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center, 2013.

Stroup, Sheila. “Zulu Coconuts, Always a Favorite Mardi Gras Throw, Are Priceless.” Mardigras.com, The Times-Picayune, 15 Feb. 2015, www.mardigras.com/new_orleans_parades/article_bd8910b9-2c59-5e91-81c1-223dd50d2bc6.html.

Taylor, Yuval, and Jake Austen. Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop. W.W. Norton & Company, 2012.

Vinson, Robert Trent and Robert Edgar. “Zulus Abroad: Cultural Representation Education Experiences of Zulus in America, 1880-1945.” Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 43-62. Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 2007.