Ukiyo-e style art originated in Japan in the 17th century. Characterized by bright colors, extravagantly dressed figures and beautiful landscapes it was adopted in the 19th century by other nations and the style was incorporated into everyday western life. The French term, Japonisme, refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design in western Europe in the nineteenth century. French art critic and collector, Philippe Burty is attributed with coining the term in 1872.

Prior to this, Japan entered an era of seclusion during the Edo period which lasted from 1639-1858. This isolation began when shōgun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, ordered the crucifixion of Christians, and all Europeans were expelled. Japan’s borders were closed and an island for annual trade with the Dutch was built off its coast. Dutch imports were studied by Japanese artists and new techniques were formed. One of the most famous of these artisans was Kōkan who combined linear perspective with his own ukiyo-e style paintings and prints. Already having the skill to replicate western figures and arrangements, Kōkan had the advantage of being easily able to document some of the only meetings between political figures of Japan and the west.

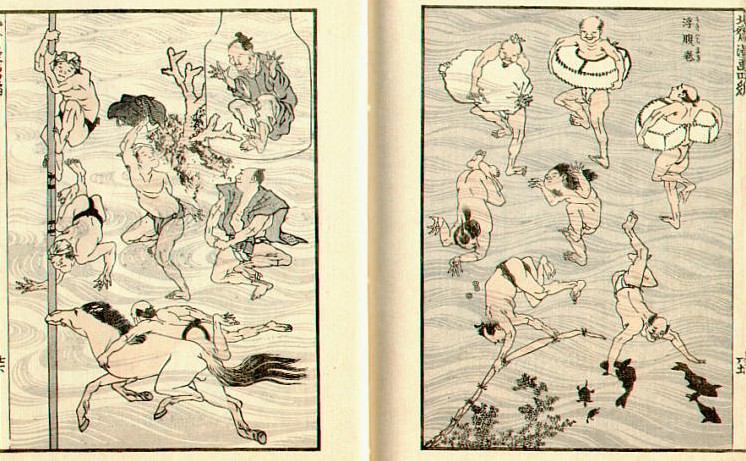

It is said that Japonisme originated when F. Braquemond of Paris came across a copy of a Hokusai Manga used for packaging porcelain in the 1850s. Hokusai Manga is a 15 volume series of sketches by Japanese artist Hokusai first published in 1814.

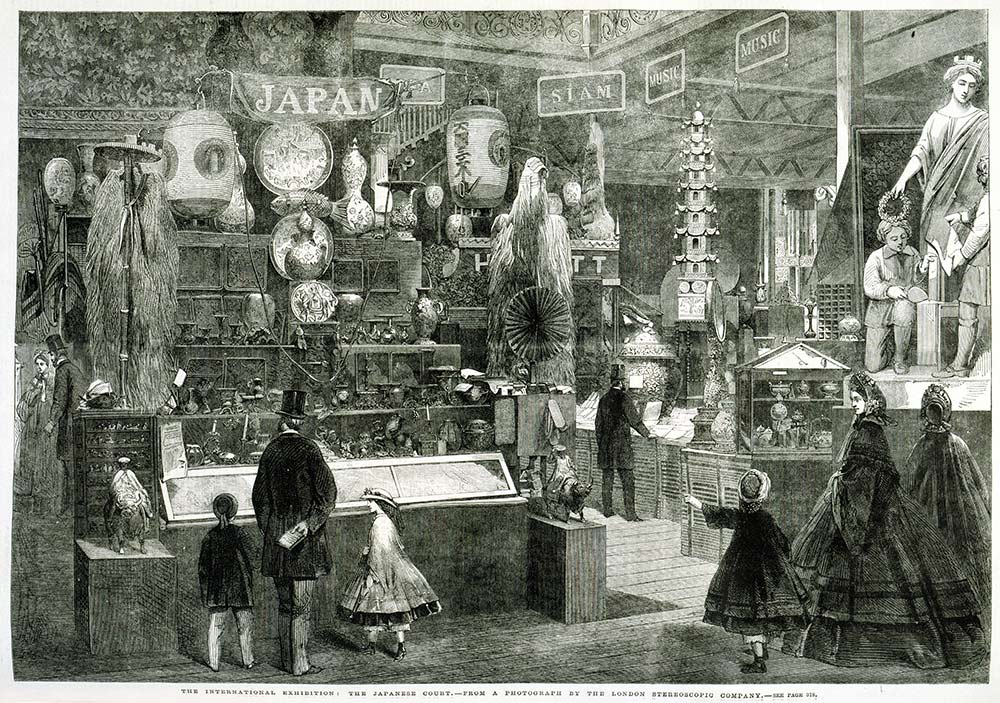

In 1862, the second London International Exhibition was held and nations from across the globe came with goods to put on display and represent themselves. Japan did not have an official booth but goods from the country were displayed by Englishman Sir Rutherford Alcock, a British diplomatic representative to Japan. exhibited various Japanese items he had collected. He made arrangements for the embassy’s dispatch to Europe and its activities in the region. His exhibits included not only industrial art products, such as lacquered japan ware and swords, but also straw raincoats, lanterns and straw sandals. While these items were highly praised by European people, they were received differently by the Japanese embassy members. The Japanese embassy, upon seeing what items were being displayed felt it was a negative representation. One member, Tokuzo Fuchibe, said, “they had been like old bric-a-brac and that all the Japanese exhibits had been very shabby.”

In the 1860s, Ukiyo-e style art from Japan was widely disseminated in France. Westerners were fascinated with these items and western artists documented this fascination. A prime example of this is James Tissot’s Young Ladies Looking at Japanese Objects. In this painting, two beautifully dressed women crowd around an intricate model of a boat. The boat sits atop a table covered in a japanese silk table cloth. Behind them is a Japanese painting of courtesans. Tissot represents the popular curiosity about Japanese items in Europe.

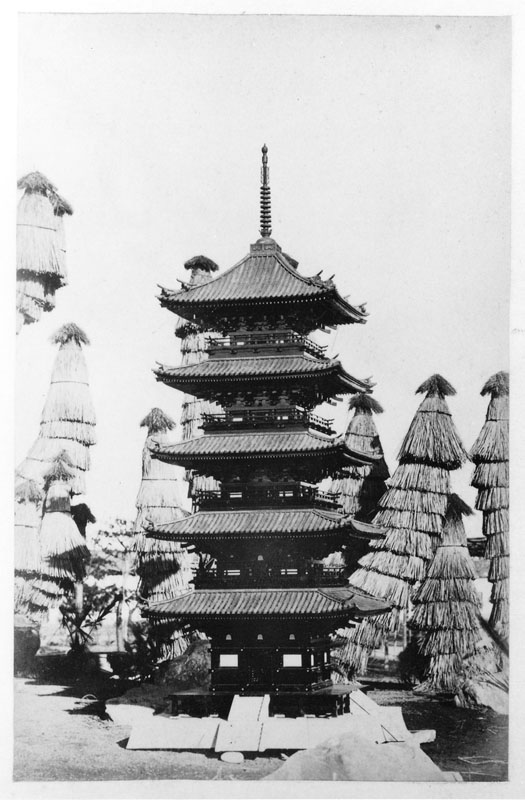

The first international exposition for the modern Japanese government in the Meiji period to officially participate in. the government built a Shinto shrine and a Japanese garden featuring a white wooden gate. Behind the gate were the shrine’s main structure, a traditional music and dance hall, and an arched bridge. At the Industrial Pavilion, the government exhibited ukiyoe works and industrial art products. The exhibits that drew public attention included the Kinshachi (golden dolphins) of Nagoya Castle, a model of the Great Buddha of Kamakura,a model of the approx. four-meter high five-story pagoda of Tennoji Temple of Yanaka, Tokyo, a big drum approx. two meters in diameter, and a lantern approx. four meters in diameter with a picture of a dragon on a waterfall.

The Portrait of Père Tanguy by Vincent Van Gogh from 1887 serves as an example of Ukiyo-e influence in Western art. The bright colors of the painting and the Japanese prints that hang behind the male figure clearly demonstrate the presence of Ukiyo-e.

– Chloe Coleman